For years, retirement lived in my head as a clean transition. Finish strong, downshift, start traveling with a clear plan and an open calendar. What I did not plan for was pneumonia taking five weeks of the timeline I did not have to spare.

This is my second retirement. The first time, about a decade ago, I sold a yarn shop, closed a photo studio, moved to Las Vegas, and rode a bicycle almost every day for six months until I got bored and wanted play money. This time the plan was different — less pause, more pivot. Keep a fractional CTO position. Work on a few part-time projects. But commit, fully, to at least a year of world travel with M.E.

I know myself well enough to know I need to be doing something. But I also know what it feels like when most of what you considered broken has been fixed, the numbers are good, the projects have either concluded or are finally underway, and a re-org opens a clean seam to step through. December 2025 was that seam.

I decided, 100%, on December 24th. Not tentatively, not “let’s see how Q1 goes.” The kind of decided where you feel the weight lift off your chest and the future rearranges itself into something you actually want to walk into. M.E. and I had talked about this for a long time. We’d both traveled extensively before. We both love the feeling of just being somewhere else, where the rhythm of daily life is a little different. Not rushing through highlights, but staying long enough to find routines — a month per country, maybe longer if we loved it. A year, at least.

December 24th was the day it stopped being a conversation and became a decision.

I got sick on December 26th.

It Started as a Cold

At first it was just a very bad cold, the kind you push fluids and wait out. Then came the ear pressure, then the ear pain. By 3 AM on Friday, January 2nd, I was awake and searching for an available appointment. I got into a primary care office that morning. I was losing hearing on the left side. Middle ear infection. Amoxicillin, prednisone, move on.

By that afternoon, my left eye was infected — painful, red, worsening fast. A video appointment got me antibiotic drops, but by evening the eye had swollen shut. That was a bad few hours. But topical antibiotics are genuinely remarkable; it cleared in just over 24 hours and stayed clear.

Coming from a medical family—my grandfather, Chauncey D. Leake, both of my parents in medicine, and my own major in human anatomy, I’ve always found the history of penicillin fascinating, but watching an eye infection clear that quickly brought back a real sense of awe for antibiotics that everyday familiarity can make easy to forget.

The prednisone masked a lot of what was building underneath. A cough started and deepened. By Tuesday, January 6th, the ear pain had intensified, the right side was now affected, and a new symptom had arrived: chest pain. Not subtle. Getting-up-there-on-par-with-a-broken-bone chest pain.

But what scared me most wasn’t the chest. It was the hearing. I had almost none on the left side and the right wasn’t great. I was weeks away from boarding a plane to the other side of the world, and I was going deaf.

Inner ear infection. Ear drop antibiotics. More prednisone.

The X-Ray

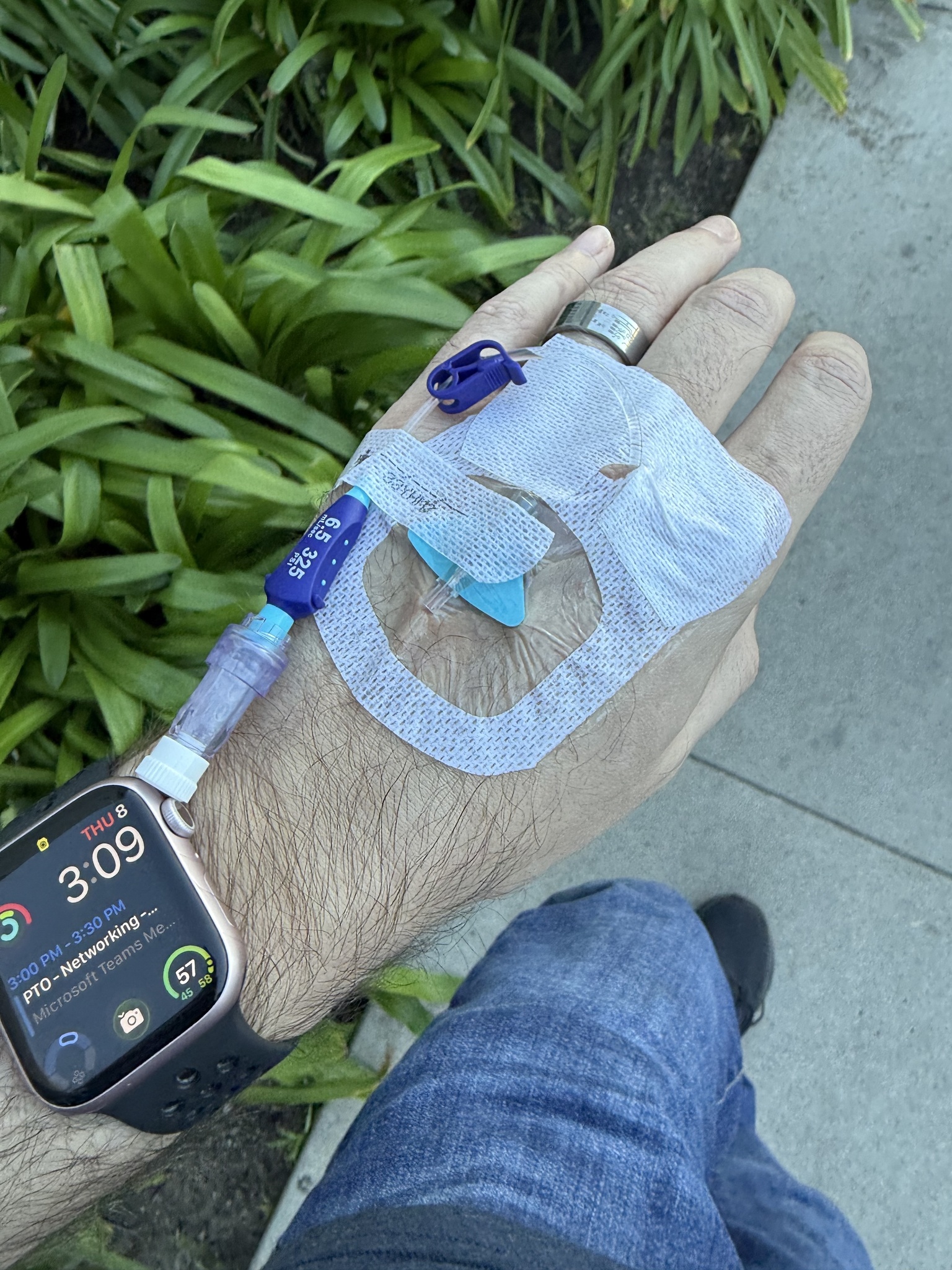

Thursday, January 8th. The chest pain had become impossible to set aside, and the cough was relentless. They ordered an X-ray.

What came back was, to use a clinical understatement, concerning. Immediate CT scan. The kind of speed that does not make you feel better about the situation.

The CT ruled out the worst of what the X-ray had suggested — previous scarring and a granuloma from COVID in 2020, not the alternatives they were screening for. Nothing quite like pneumonia in three lobes being the good news diagnosis.

Two oral antibiotics. An IV antibiotic. Three separate blood draws. IV fluids.

There was significant improvement over the next couple of days, but it didn’t hold. The weekend was a slide back down. Monday the 19th was awful — one of those days where you’re measuring yourself against the previous version of sick-you and losing. Bloodwork was elevated but not as extreme as it had been, which created its own uncertainty: was it still trending down, or had it turned around and started climbing again?

Two more antibiotics. That made eight or nine total, depending on how you count. More prednisone. Inhaled steroids. Use the previously prescribed albuterol every four hours regardless of symptoms. Same with the cough suppressants. Keep taking every single prescription and non-prescription allergy medication I had, regardless of whether those symptoms were active.

This time, it worked. Four or five days into the new regimen, I started to feel meaningfully better.

What It Took

Looking back, the arc of it is clearer than it felt at the time. In the moment, it was a repeating pattern of improvement followed by degradation — you’d feel a little better, then worse again, then a little better, then worse again. It felt like the illness was renegotiating terms every few days, and you were never sure which version of you would show up the next morning.

In retrospect, most of what I interpreted as “getting better” was the prednisone doing its job. The steroid was carrying me, and I was mistaking its strength for mine. When things got bad enough that even the prednisone couldn’t cover the symptoms, that was when it was truly bad. It was mostly just bad, and mostly so for a long time.

There were two categories of fear running in parallel. The first was medical — real, visceral concern about my hearing and my eyesight, compounded by the fact that I was about to need both for a year of international travel. Having an eye swell shut when you’re weeks from a departure date is not an abstract problem. Losing hearing in one ear while trying to plan a life that depends on being present and attentive in unfamiliar places is not abstract either. These weren’t “what if” worries. They were happening.

The second was the slow-building frustration of falling further and further behind. First because more symptoms kept arriving — every few days brought something new to manage — and then simply because I wasn’t getting better. I could see the calendar moving. I could see the tasks not getting done. And I could not do anything about either.

The Planning That Didn’t Happen

I am spreadsheet-first. Checklists, timelines, structured plans, conditional logic. It is how I manage anxiety and how I make complex logistics feel possible. I don’t wing things. I build systems, and then I execute them (and an apology to every engineer who’s worked with me over the last 20–30 years and had to hear me connect aviation and medicine to systems deployment at least once — there is real overlap, and while I can’t find the late 1990s/early 2000s study I tend to cite: Systems Thinking in Aviation and Healthcare).

During those five weeks, I could do none of it.

I was making decisions about my two weeks’ notice from bed, heavily medicated, on sick days. The math of it had its own dark comedy: I realized the Friday I got my first diagnosis that the following Monday was a holiday, and I didn’t want to give less than two weeks. So I was doing professional arithmetic through a fog of prednisone and amoxicillin, trying to land on a last day that felt respectful. January 30th. I used all of my 2026 sick leave and still had a pile of work deliverables to close out.

The original departure date from LA was February 14th. There was no real plan beyond that — just dates in a countdown app. All of the planning was supposed to happen in January: movers, selling the cars, deciding what to take and what to store, documentation, logistics. January was supposed to be the month I turned the decision into reality.

January was gone.

I still can’t find the title to one of the cars. That’ll have to get solved remotely now.

The thing about losing time when you have very little of it is that you can’t just compress the remaining work into fewer days. Time is the basic solution to most problems. Without it, you end up solving things with money instead, and some problems take both time and money, which makes them temporarily impossible. You just have to accept that some things won’t be done right, or won’t be done at all, and that “good enough to move forward” is the only standard available to you.

M.E. bore most of the weight of this. While I was in bed unable to contribute spreadsheets or physical effort or even clear thinking, she was trying to understand what our life was about to look like and hold the timelines we’d planned for together. The frustration between us wasn’t conflict exactly — it was shared helplessness. We are both planners married to each other. Neither of us could plan. That’s a specific kind of hard.

What Changed

I did not abandon anything. But the design changed.

The February 14th move to the Olympic Peninsula stayed exactly the same. What changed was everything after that: we hadn’t booked a flight, an Airbnb, or even locked where the next destination would be, because we needed more runway in the U.S. to coordinate contractors, finalize sales, and close out logistics cleanly.

The Peninsula is still where I mostly grew up, and still the place I’ve always used as a jumping-off point. Even when I hadn’t lived there for years, it was where I’d go back to before starting the next thing. Stay for a bit — sometimes days, sometimes weeks — get grounded, and then leave again. It still feels right for this transition.

Just last week, I booked a flight to Cebu City and an Airbnb. It’s warm, it’s in the direction we’re headed, there’s an expat community, high English proficiency, and it looks beautiful. It seemed like a good way to ease back into travel after everything.

Booking that felt really good. Not because of the destination specifically, but because it felt like I was finally catching up. After weeks of falling behind on everything, each small thing I check off gives me a dopamine hit I’m not ashamed of.

Beyond Cebu, probably Thailand. Then Kazakhstan to meet some friends — that’s the only fixed point on the calendar. The rest, we’ll figure out. The plan right now is roughly one month per country. If we find somewhere we love, we stay longer or plan to return.

I’m still about five or six weeks out from a follow-up CT scan to confirm my lungs have fully cleared — COBRA-ing my healthcare to make that happen. Recovery from pneumonia is not a line graph trending upward. It’s more like weather — you get a stretch of good days and start to trust it, and then a bad day reminds you that your body is still doing repair work you can’t see or schedule.

The muscle depletion has been its own strange chapter. Five weeks of near-total inactivity strips you in ways I didn’t expect. Walking up a flight of stairs gave me DOMS like I’d done a full-body workout. Carrying boxes to the car felt like an athletic event. There are still bouts of lightheadedness and occasional vertigo, and it’s honestly hard to tell those two apart. The body just takes its time, and it doesn’t care about your countdown app.

But I’m moving. Things are getting done. Not all of them, and not on the original timeline, but enough.

What I’d Say About It

I wouldn’t frame this as advice. But if you’re someone who has made a big life decision and then gotten hit with something that threatens to derail it, here is what I know now that I didn’t know on December 24th:

With enough force of will, most things work out. Pivots are okay. It’s basically the same as any other impossible deadline — it’s not going to be implemented exactly how the whiteboard said, but it’s going to be Good Enough™ to move forward.

The plan changed. The direction didn’t. And if I’ve learned anything from two retirements before 45, it’s that direction matters more than the plan.

This is the first in what will probably be a series — some posts here, some on M.E.’s travel site — as we figure out what a year of slow travel actually looks like in practice. More to come from Cebu, and wherever we end up after that.