Issues Presented by Geographical DNS

DNS, the Domain Name System, has become something of a Swiss Army Knife of networking and systems engineering. One of the tools in this set determines a user’s location, and then send an IP address of a nearby server that can service the request.

On the surface, this seems like a great idea. Let us dig deeper and see what it can break.

First off, this is not a discussion on what we should or should not do with any protocol. I’m not going to stand on a soapbox and say that using DNS for geographic targeting is bad (or good) or discuss any of the other ways that DNS has been used, extended, or twisted from what some consider its pure beginnings.

What GeoDNS is

When you attempt to reach a website, your computer initially sends a query to map the human-readable domain name to the machine-readable IP address. When using a regular internet service this goes to a DNS server that is nearby to you (see my article on Anycast for how this works), either to your ISP or to a public provider like Google (8.8.8.8/8.8.4.4), Cloudflare (1.1.1.1), or CenturyLink(4.2.2.2). This server will then make a recursive query, reaching the authoritative server that is configured to reply for the domain name, and it will return that IP address to your computer.

When you attempt to reach a website, your computer initially sends a query to map the human-readable domain name to the machine-readable IP address. When using a regular internet service this goes to a DNS server that is nearby to you (see my article on Anycast for how this works), either to your ISP or to a public provider like Google (8.8.8.8/8.8.4.4), Cloudflare (1.1.1.1), or CenturyLink(4.2.2.2). This server will then make a recursive query, reaching the authoritative server that is configured to reply for the domain name, and it will return that IP address to your computer.

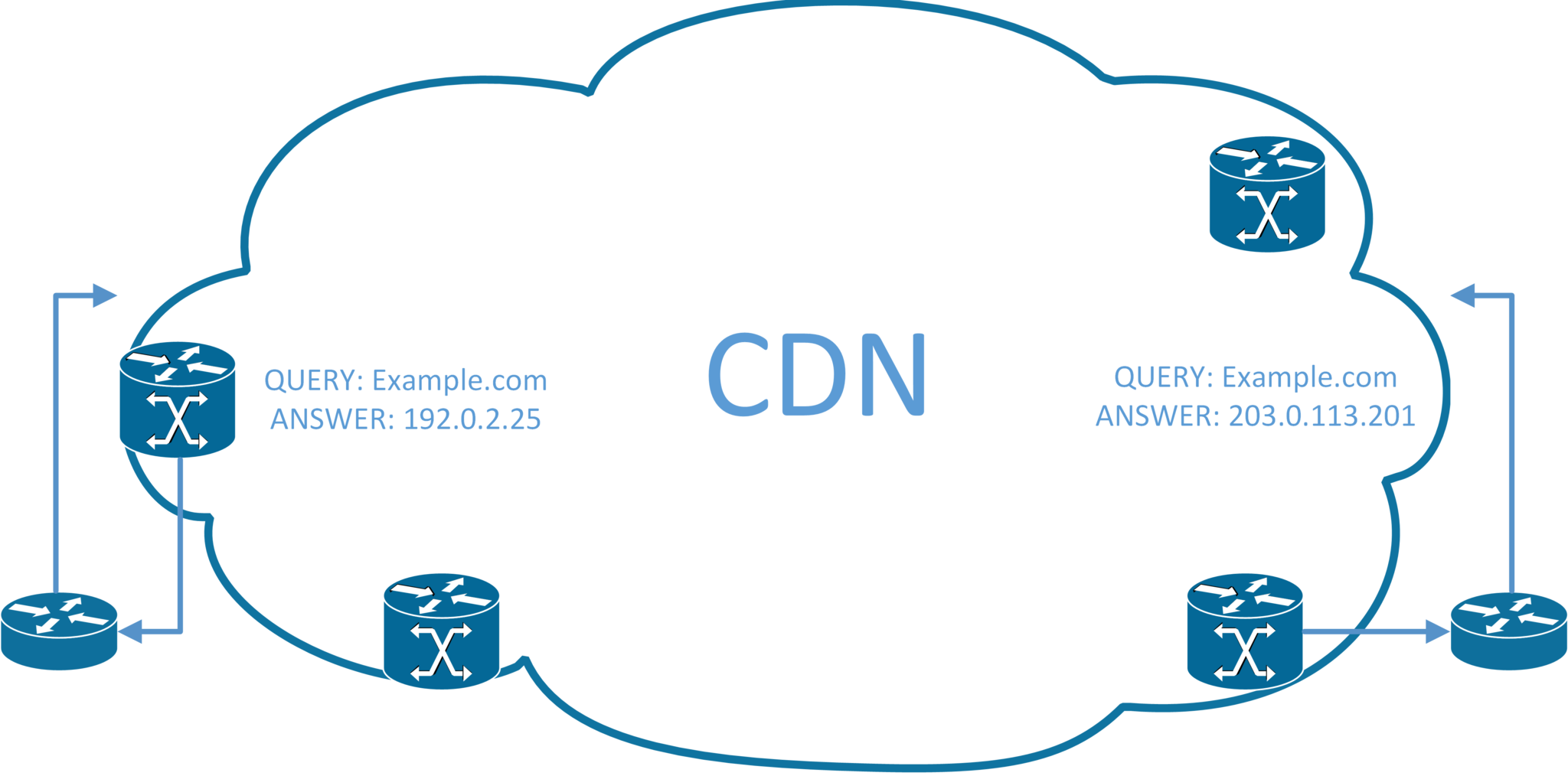

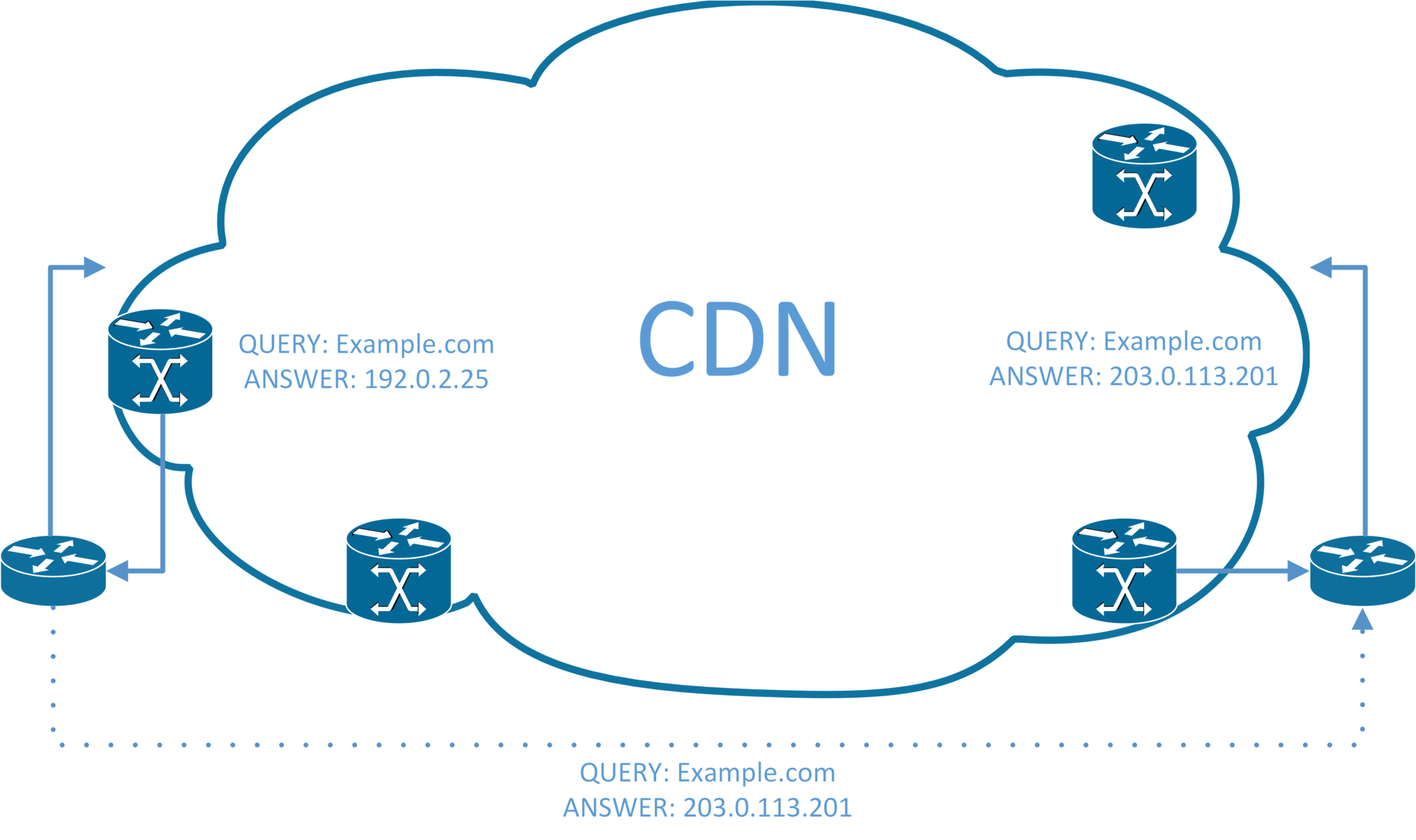

Even at the speed of light, it takes an appreciable fraction of a second to reach a server on the other side of the world, so today most websites are served by Content Delivery Networks, CDNs. CDNs have copies of the website cached around the world so they can serve it from a location that is closer to the user. GeoDNS is one of these solutions.

For a CDN, the authoritative DNS server is also Anycast, in the same datacenter as the local content, and will be configured with the IP addresses of the servers locally hosting those websites. Nothing else has to happen, you’ll receive content that is cached near to you because you queried a server that was near to you.

How GeoDNS breaks

Lots of things can break GeoDNS, this increases the load on long-distance links, slows down website loading for users, etc. These aren’t the end of the world. There is, though, one particular way that it breaks and then causes websites to entirely fail to load. (There’s probably more, but this is the one that drives me batty so regularly).

Lots of things can break GeoDNS, this increases the load on long-distance links, slows down website loading for users, etc. These aren’t the end of the world. There is, though, one particular way that it breaks and then causes websites to entirely fail to load. (There’s probably more, but this is the one that drives me batty so regularly).

Corporate enterprise networks do two specific things that can interact badly with GeoDNS:

- Centralized DNS infrastructure

- Restrictive Firewall Policies

Centralized DNS can come about either from a security implementation standpoint (definitely fodder for a future article, DNS today is generally sent entirely cleartext) or simply because the Microsoft Active Directory and Domain controllers historically rely heavily on DNS (maybe another article here?). In the latter case, a local DC will generally recurse all requests to centralized infrastructure.

On a home network, firewalls tend to be configured to allow any traffic outbound and only to restrict inbound traffic. This saves configuring any application-specific rules but doesn’t stop local computers from exfiltrating data or “dialing home” if they are compromised (a major requirement of most attacks). Enterprises will generally restrict some outbound access on all networks, and then have very restrictive networks that lockdown most or all outbound traffic.

When services tended to be tied to a handful of specific servers, these restrictive policies were easy to implement. These IP addresses can communicate in that direction to those IP addresses on this port. Unfortunately, those days are over, killed off by the Cloud and CDNs.

Modern Firewall Policies for CDNs

Some companies still publish a list of IP addresses for their servers. These are generally programmatically generated, automatically updated, and in a machine-readable format. Such as Amazon’s List of AWS IPs. These are the gold standard for security, but difficult (or impossible) to implement for the average engineer with normal equipment so I’m leaving that as an exercise for the reader.

What most firewalls today have done instead is implement some form of Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN) policy capability. Instead of writing a policy for specific IP addresses, you can put in the FQDN in a human-readable format and let the firewall take care of it.

How firewalls implement FQDN Policies

There are three major ways to implement an FQDN policy, with varying effectiveness depending on the specific types of traffic.

Make a DNS Query

When you just simply implement a policy, many brands of firewall will simply make DNS queries from time to time and cache the results as IP addresses and apply those to the policy.

At the time of writing this is done by Palo Alto, Fortinet, and others.

This is one of the most reliable methods, but the most likely to get bitten by GeoDNS issues.

Sniff DNS Traffic

Some firewalls will intercept the plain text DNS Query and Responses and use these to add IP addresses to the policies.

This requires the DNS query to pass through the firewall as plain text. It eliminates the ability to do most forms of centralized DNS management, implement quite a lot of Active Directory, and generally makes you question security.

As we move to newer (again, I’m not debating these here) DNS technologies such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) extensions, DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH), or other forms of encrypted name lookup this becomes impossible.

At the time of writing Meraki is the only brand I know of doing this.

On the plus side, it generally will simply break on a corporate network and if it doesn’t break it isn’t generally susceptible to GeoDNS issues. It also allows for * in the FQDN.

Sniff HTTP(S) Traffic

The HTTP1.1 spec used by most browsers and websites encodes the FQDN in the header of every packet. A firewall can simply look for this and know what site the browser is asking for.

HTTPS and TLS both suffer from various leaks to domain information in headers during establishment. These leaks send the domain as plain text and allow a firewall to sniff the traffic and know what site is being requested.

This is used by nearly every firewall I know of at the time of this writing, but only when a policy is implemented as URL Filtering. As suggested by the method, this only works on HTTP(S) traffic, any other protocols must be allowed by a separate policy. It also allows for * in the FQDN.

This is the most common technique for oppressive governments to implement site blocking. As such it is commonly spoofed and should not be considered valid as the only form of policy implementation. (Fodder for a future post: why FQDN Splat Policies are BAD).

Results of GeoDNS Breaking

The results are pretty simple. The firewall implements the policy incorrectly.

This is fine from a security perspective because it will implement it with valid IP addresses that should have been allowed.

From a user perspective, though, this is not fine. In the example above, the firewall is making a query for example.com and receiving 192.0.2.25, it correctly implements a policy and allows traffic to that IP.

However, the user receives 203.0.113.201 for the same DNS request, which points to a different datacenter serving the same content. The firewall doesn’t know what server this is, and so blocks the traffic flow.

Workarounds

Fortunately, the workarounds are fairly simple. Implementation, though, will depend on your corporate policies, specific configuration, and available equipment. Most require some combination to achieve the desired effect.

Normal provisions for running lab or pilot (in a location you can physically reach, in case it really goes sideways!) are definitely advised.

Set the firewall and clients to the same public DNS

If everything is using internet-based DNS, this should simply be your default configuration. Set DHCP to hand out the publically accessible DNS that is on the internet side of the firewall and set the firewall for the same. This is the normal config on most networks and likely you wouldn’t be reading this article if this applied to you.

If you will still rely on DNS for your Intrusion Detection System/Intrusion Prevention System (IDS/IPS) then you will need to have satellite local installations of this monitoring DNS.

Set the firewall and the clients to the same private DNS

If you have publically addressed private DNS servers, you can set them to allow traffic from your firewall and respond appropriately. This is potentially a significant amount of configuration.

If you have privately addressed DNS servers available across a provider MPLS solution this may be the easiest and best way to go. (If 100% of the site traffic is passing that MPLS solution, you should already be doing this and likely would never read this article).

Where it becomes tricky is if you have private DNS servers that are available after some type of VPN tunnel comes up. This also applies to pointing the firewall at local DNS servers that might always recurse into a tunnel. If that tunnel does not come up you will not have DNS and despite the links being up, the users at the site will be filing a lot of tickets because they can’t reach the internet.

If you point it at a local or private DNS relying on a tunnel that is facing an FQDN instead of an IP address… You have just cut the site off the moment that the tunnel goes down. You may now only have minutes to develop an out-of-band solution that does not rely on the tunnel or DNS entries. I don’t have an article for this yet. Go now and book your plane tickets to the site.

Point DNS at the firewall

This will guarantee that the firewall and client computers are in sync over DNS, but not all firewalls support acting as DNS servers.

Conditional forwarding

Set your local DNS servers to recurse to different servers for different domains. For instance to a local or cloud DC for your domains and Google’s 8.8.8.8 or the firewall for everything else.

Combine this with one of the above for a solid solution.

Closing notes

Geographical DNS is with us for the foreseeable future. It’s an inexpensive solution that for the vast majority of internet users is a quality of life improvement.

On a longer-term we are seeing websites themselves with Anycast delivery, letting the routing protocols bring the content closer to the user rather than shoehorn functionality into something never designed to support it. Anycast is even directly in the IPv6 Specifications.

Want to know more about Anycast? Read my article on Anycast.

Want to discuss it? Head over to LinkedIn

This is my first full-length article in years, I’d welcome all feedback: LinkedIn is effectively the only Social Media platform I’m on, but you can try to tweet at me and I reply to Keybase quite quickly.

About John

This is my website, so you'll see this on most posts. This is also a really awkward photo of me I took a couple of years ago when I thought I needed a more professional profile photo. If you'd like to know more I have an About Me section. I think it's funny.